Trade Unionist

In the latter half of his career in politics, Michael Manley repeatedly said that the best years of his working life were those he spent in the trade-union movement. He often quipped, too, that if you cut him open and looked at his heart you would find engraved on it the word “WORKER”. And, although he was born and bred to be committed to social justice, he attributed his understanding of the depth of injustice in Jamaican society mainly to his exposure as a trade unionist to the living conditions of Jamaican workers.

In his second book, A Voice at the Workplace, Michael Manley wrote: “… Political work had brought me close to slum life in Kingston with its grim and endlessly repeated tragedy of poor housing, children and parents crowded into single rooms, and whole families undermined if not shattered by unemployment and the general conditions of shanty town life. I had not up to then had personal experience of the impact of the plantation system and the seasonal sugar crop upon rural life. For six months at a time thousands of rural families were disrupted while the men migrated to the sugar estates to earn the greater part of the year’s income cutting or loading cane. During the crop period, these workers would bunk down, literally shoulder to shoulder, in large and mainly dilapidated barracks. If the barracks were full they would have to pay an exorbitant rent for a back room in a hovel that passed for a house in one of the sugar towns like Central Village, Spanish Town, Lionel Town, May Pen, Gimme-me-bit or Hayes…”

Mr Manley was elected to the National Executive Council of the democratic socialist People’s National Party (PNP) in September 1952. Several powerful members of the party had been expelled that year, mainly on the ground that they were more marxist than democratic socialist, and the leftist-controlled Trade Union Congress (TUC) had been disaffiliated from the party. To fill the void, the PNP leadership swiftly established a more compatible trade union, the National Workers Union (NWU).

Fundamental principles

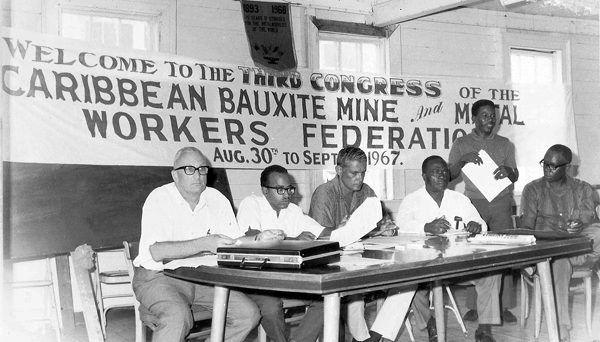

Michael Manley became the Sugar Supervisor of the new Union in 1953. In 1955, he was elected its Island Supervisor and First Vice President. He founded the Caribbean Mine & Metal Workers Federation in 1961 and was its President for thirteen years. A legendary trade unionist who brought unprecedented creativity and energy to his work, Manley earned great benefits for NWU-member workers and won acceptance for fundamental principles affecting employer-employee relations that applied not only to the workers he represented but to the entire country.

In 1953, the NWU won recognition of the principle that wages in the bauxite and alumina industry should be based on the companies’ ability to pay rather than on parity with other wages. The result was a 300-per cent increase in bauxite/alumina workers’ wages.

In 1959 Manley proved that Jamaica’s sugar industry had made £2 million of unreported profits and forced a £1.25 million wage increase. Perhaps more important was the fact that the Goldenberg Commission, which resolved a 1950s dispute between the Sugar Manufacturers’ Association (SMA) and the unions representing workers in the sugar industry, established the principle that the workers’ representatives have a right of access to the accounts of the enterprise of which they are a part.

In 1964, Michael Manley led a 97-day strike, one of the longest in Jamaica’s history, following the dismissal of two journalists at the state-owned Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (JBC). Contending that the dismissals were arbitrary and unjust, Manley, a handsome six-footer, fearless leader and spellbinding orator, now enjoying the status of Senator, led a civil disobedience campaign that resonated throughout Jamaica. When he lay down on Kingston’s streets in the path of peak-hour traffic, he was joined by masses of Jamaicans of all classes, including some of his critics and supporters of the Government, who were perceived as the instigators of the dismissals.

The authorities tear-gassed demonstrators and refused to negotiate. Manley’s call for a nationwide strike met with considerable early support. The Government promptly established a Commission of Inquiry, which in effect came to a split decision, on balance more in favour of the JBC. Although clearly dissatisfied with the outcome, Manley reflected in A Voice at the Workplace: “… The strike marked the end of the first phase of the struggle for the democratisation of the workplace… After the strike, Jamaica embarked upon the second phase of the process where the right to continue in a job was no longer regarded as being subject to arbitrary unilateral employer decision…”

Unification and modernisation

Michael Manley’s championing of workers’ causes did not end with the successful strikes he called and the worker education he pioneered as a trade unionist nor with the raft of labour legislation he fathered as Prime Minister in the 1970s. Working with Hugh Shearer and other trade unionists, he made a monumental contribution to the eradication of destructive trade-union rivalry and knee-jerk anti-capital attitudes. He and his colleagues in leadership steered the trade-union movement towards unification and modernisation, resulting in such phenomena as the National Housing Trust, the Jamaica Confederation of Trade Unions, the establishment of the Trade Union Education Institute at the University of the West Indies (UWI), now the Hugh Lawson Shearer Trade Union Education Institute, and the memoranda of understanding that have become a critical element in collective bargaining.

The raft of labour-related legislation that Michael Manley initiated during his first period as Prime Minister, in the 1970s, reflected his trade union background and experience and, as well as securing the rights of unionised workers, brought the force of law to benefit workers who were not unionised.